A journeyman scientist recalls his stops along the way at sodium-22, improv, airborne instruments, and NASA satellites

Unlike most of us, scientist and science leader Jeff Stehr can remember the first joke he ever made up―a pun that he says drove a double-class of his fourth-grade classmates wild.

Humor (and its uses) have threaded through his life since then, from studies in physics and atmospheric science to stints at the University of Maryland, NASA, and consultants Booz Allen Hamilton. And don’t forget Stehr’s spare-time improv gig from 2008 to 2015 at The Comedy Spot in Arlington, Virginia.

Improv, he says, “has served me extraordinarily well in everything I’ve done.”

That wide net of experience led Stehr in November 2019 to become the newest program manager for the Atmospheric System Research program (ASR) at the U.S. Department of Energy.

ASR supports research into the atmospheric processes that determine how much solar radiation reaches the Earth and how the planet’s hydrological cycle works.

Part of that means improving the predictive acuity of Earth system models and the stubborn uncertainties within them. And part of that means improving our understanding of precipitation, clouds, radiative transfer, and aerosols―the tiny liquid or solid particles in the air that play a role in cloud formation and radiative scattering.

Down the hallway from Stehr at ASR’s Germantown, Maryland, offices is the other program manager, five-year veteran Shaima Nasiri, an atmospheric scientist who in her days at Texas A&M University specialized in cloud and aerosol remote sensing.

Her new colleague brings a lot to the ASR table, she says, including “enthusiasm, a background in aerosol measurements, an understanding of the federal landscape, and some real organizational and communication skills.”

Just in time, too. Stehr arrived at ASR the same month the program put out a call for 2020 research grant applications.

“Over the Moon’

Stehr got a phone call and email offering him the ASR job in August 2019.

“I was simply over the moon,” he says. “I said: ‘Absolutely. I will accept. I saw this as more than a job opening. It was a calling.’ ”

Stehr says his new role puts him at the center of “the atmospheric science and climate that are really going to start driving decisions whether we want it or not.”

Driving his own decision to be a scientist required, in part, a stinkbug or two.

Stehr’s father Fred, now 87, is a retired professor of entomology at Michigan State University, where he is regarded as a world authority on immature insects.

Stehr the son relates that “one of my earliest memories of science were of my father sticking a stinkbug in my face and saying, ‘Do you know what this is?’ “

Same with the large wood boring beetle that lunched on a finger the younger Stehr put in harm’s way. And the giant butterfly specimen with wings the size of a bat’s that wowed his classmates when his father visited the grade school.

Pausing at Positronium

By the time Stehr was ready for college (the University of Michigan, B.S. 1989), it was not biology that captivated him. “Too much memorization,” he says.

And it wasn’t the electrical engineering that he started out in, with the thought he would design computers one day. That first class in circuits was enough to drive him to another major.

Stehr’s choice for a degree track turned out to be physics―in particular, atomic and molecular physics. He spent a lot of time in what was then the Ford Nuclear Reactor on campus as part of a group working on positronium, an exotic two-particle atom that in its longest of two life spans decays in 142 nanoseconds.

His undergraduate thesis identified sodium-22 as a better source of positrons for what Stehr calls “the simplest atom in the world.”

He entered the University of Minnesota (PhD, 1995) for doctoral work in high-energy physics, but felt glum after a seminar on something called the isospin of the omega-minus particle.

Luckily, a seminar series for new PhD students featured a talk on ozone by Konrad Mauersberger, the professor who would eventually be his advisor on a dissertation that explored oxygen isotopes in ozone.

After the lecture, “I asked him 15 minutes of questions,” and was hooked, says Stehr. “It was a sign that maybe I shouldn’t be looking at fundamental particles. I should be doing something more societally and Earth-preservation relevant.”

Going Airborne

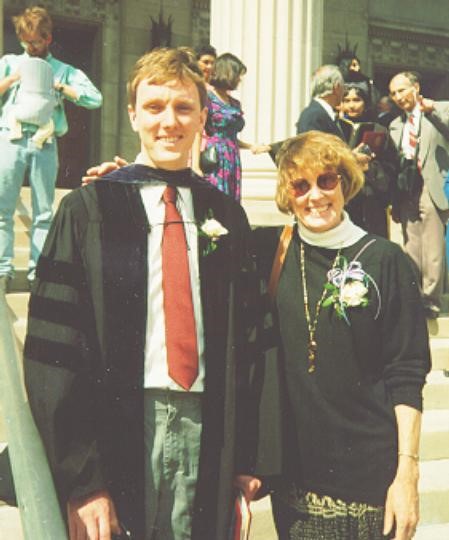

At the University of Minnesota, in a rare example of family synchronicity, Stehr received his PhD on the same stage in Northrup Auditorium that his father did in 1958 and his paternal grandfather (also an entomologist) in 1930.

Getting the PhD by investigating the isotopes of ozone made Stehr’s next step a natural one: postdoctoral research at the University of Maryland, College Park, where for several years he modeled and measured local air pollution.

He went further afield too, during the first year of NASA’s international, multi-agency 1997-1999 Indian Ocean Experiment (INDOEX), which compared satellite, air, ground, and shipborne measurements of human-produced aerosols.

Stehr spent six weeks on a NOAA ship and one week on Kaashidhoo Island in the Maldives.

“It’s the most threatened island chain in the world,” he says, where three feet of sea-level rise would wipe out a nation. “I always think about those people while I’m working.”

By 2003, Stehr was an assistant research scientist who, over the next decade, upgraded the airborne research program and founded and directed a first-ever undergraduate program in atmospheric science.

Of the first, he says, instruments got more sophisticated through the years and the airplanes the researchers used got roomier: from a four-seat Cessna 172 (the instruments were seat-belted in place); to a six-seater Piper Aztec (“Those six people must have been awfully small,” he says); to a Cessna 402B “with eight actual seats,” says Stehr. “At that point, we thought we were really living.”

That airborne era in his career was capped by a collaborative experiment in 2011, part of a series of NASA regional air quality campaigns called Deriving Information on Surface Conditions from Column and Vertically Resolved Observations Relevant to Air Quality (DISCOVER-AQ).

Deriving Information on Surface Conditions from Column and Vertically Resolved Observations Relevant to Air Quality.

series of DISCOVER-AQ campaigns designed to diagnose urban air quality.

A Worker Bee

While still at the University of Maryland, Stehr was a lobbyist, the author of science documentation, an expert witness, and a science commentator. (He has appeared in three National Geographic Channel specials.)

In late 2013, Stehr left university life to become a lead associate and then a senior lead scientist at the Virginia-based consulting company Booz Allen Hamilton, where he was tasked to support NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C.

That interval, which lasted until Stehr arrived at ASR two months ago, included work in Applied Sciences with the NASA Disasters Program (to predict and respond to natural and technological disasters); with NASA’s Heliophysics Science Division (to study the sun’s extended environment).

He was also developer and coordinator of NASA’s 14-agency Satellite Needs Assessment team (where he met Nasiri, who represented DOE).

“I wanted to be a worker bee,” says Stehr of his early NASA-Booz Allen years, “and help people communicate science.”

The main keys to that kind of communication “get back to improv―being able to read your audience and listen to your audience,” he says. “You can either show somebody how smart you are, or you can teach somebody something.”

Making Something Wonderful

You might ask: Improv and science?

“They are complementary,” says Stehr. “Science is an inherently creative endeavor―and improv gives you fearlessness. It gives you listening ability. It teaches you the art of really good questions.”

In his 30s, with the PhD behind him, Stehr hankered for the kind of comedy that had brought him that storm of applause in fourth grade―and that matched the power of Tonight Show monologues in the era of Johnny Carson, who was “one of my earliest heroes,” he says.

But more fun (and applause) came from improv comedy.

“I have used those (improv) principles so many times,” says Stehr of his science communications and leadership work. “You’re taking input from the audience, listening, and building on what they give you. Together you can make something wonderful.”

# # #This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, through the Biological and Environmental Research program as part of the Atmospheric System Research program.